Phil Skewes, Associate Curator Collections Inventory, Canterbury Museum

The world’s oceans and seas have long been seen as vast and mysterious, awe-inspiring and terrifying. Obstacles that encircle us, asking to be breached. As humanity migrated across the globe people found ways to overcome those obstacles, developing seagoing craft for exploration, transportation and recreation.

Sailing ships have been used for centuries to carry people and produce over the world’s seas. Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the fastest way to sail from Australia to England was to hitch a ride east on the Roaring Forties, the strong westerly winds found circling low in the Southern Hemisphere between the latitudes of 40 and 50 degrees. The route took ships on a risky and tempestuous passage south of Aotearoa New Zealand and through the scattering of sub-Antarctic Islands that lie there.

Inevitably, these islands became the final resting places of many ships, which were wrecked on the islands’ rocky coastlines leaving survivors to battle their own way onto shore. Even if they were fortunate enough to make it to land, the environment was harsh. With no shelter from wind, rain and cold, survival was difficult. To improve their chances, the New Zealand Government established castaway depots on some of the islands towards the end of the nineteenth century. These were usually a basic building stocked with food, clothing and - of course - matches. Simple items that would save lives.

-

-

Taonga | Item

Food Depot for Castaways, Port Ross, Auckland Islands

Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena

-

-

To deter sealers and other potential thieves from raiding the stores, the clothing was often made from a distinctively patterned material, easily recognisable to the authorities. One Government official particularly protective of his efforts left a warning message at one of the depots: “The curse of the widow and fatherless light upon the man that breaks open this box, whilst he has a ship at his back”. Signs, often in the shape of a pointing finger, were placed around each island indicating the way to the depot.

Between 1877 and 1927 depots were serviced by Government lighthouse steamships, such as the Hinemoa, sailing regular circuits to stock them with supplies and pick up any castaways they found. It would have been with some trepidation that the crew approached each island, wondering what tragedies they might find. On the other hand, the sight of an approaching ship would have filled any castaway with intense relief and gratitude. One group of castaways who would have experienced these emotions were members of the Dundonald crew, their tale of ingenuity and perseverance quickly becoming front page news following their rescue.

Sailing from Sydney, set for England with a cargo of wheat in March 1907, the Dundonald ran into rough seas and strong winds which took her off course and onto the coast of Disappointment Island, part of the Auckland Islands group. Sixteen of the 28 crew members made it to shore, however one died soon after. This was the beginning of an eight-month saga for the remaining 15 castaways before they were rescued by the Hinemoa when she stopped at the Auckland Islands as part of a sub-Antarctic Scientific Expedition.

Discovering they were not on the main island as expected and with no depot of provisions to sustain them, the castaways hunkered down for the winter building sod shelters from the topsoil and eating partially raw birds, carefully saving their feathered skins for blankets and bones for sewing needles. A Finnish crew member cleverly used animal skin to make simple traditional shoes. However, they soon realised their best chance of survival was to get themselves to the main island and the depot located there, knowing that the supply ship would eventually return.

-

-

Taonga | Item

Photograph: Grave of Jabez Peters, Disappointment Island

New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa

-

Taonga | Item

Huts of the 'Dundonald' castaways, Disappointment Island

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

-

Taonga | Item

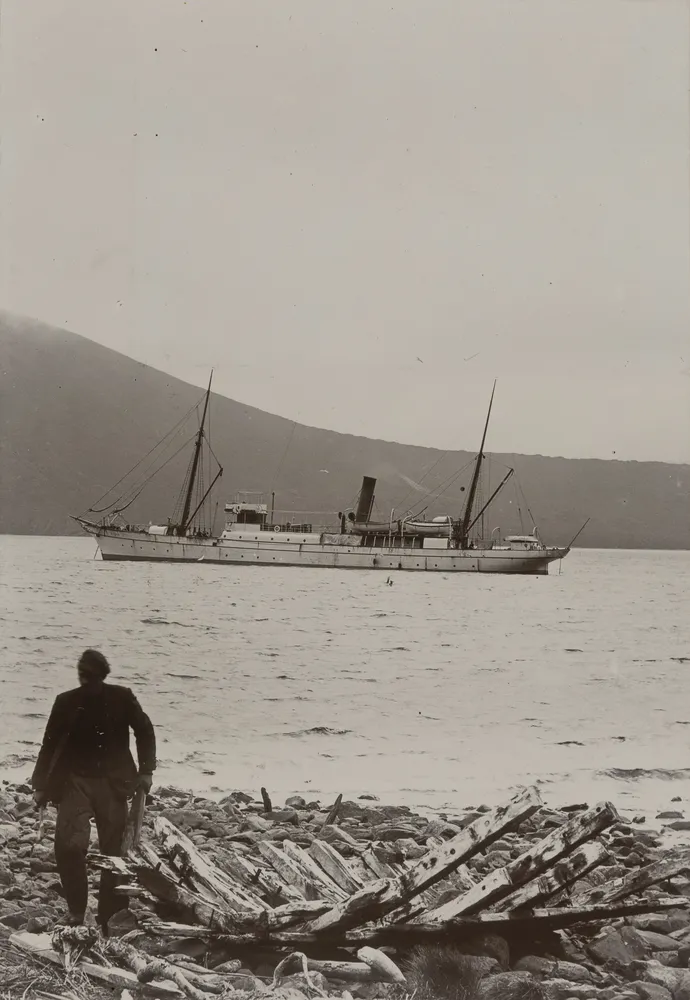

Head of Carnley Harbour. New Zealand Government steamer "Hinemoa" in background. From the album: [1907 Sub-Antarctic Expedition]; circa 1908; North, W.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

And so began an ambitious plan to build a vessel to sail across the six miles that separated them from salvation. With limited items salvaged from the wreck and only small spindly bushes growing on the island they had few resources to construct a sea-worthy vessel. Borrowing an early Welsh design they created a coracle using branches lashed together as the frame, and salvaged sails for the skin.

In October 1907, after a couple of failed attempts, four of the castaways sailed across the short but rough strait to the main island, then walked 15 miles to find the depot, helped by a sign pointing the way. Besides food, clothing and supplies, they found a note indicating that the supply ship would return shortly Importantly, there was also a small boat stored there, enabling them to return and ferry over the rest of the castaway group. What luxury to have better food, new clothing and a solid roof over their heads after months of deprivation on Disappointment Island, before they were picked up the Hinemoa a month later .

-

Taonga | Item

Auckland Island flagstaff built by Dundonald survivors at the depot, Port Ross.

Auckland War Memorial Museum

-

-

-

Taonga | Item

Framework of boat originally covered with sea-lion skins, in which Dundonald survivors crossed from Disappointment to Auckland Is. 1907.

Auckland War Memorial Museum

While many perished on the inhospitable coasts of sub-Antarctic islands, without the provision of depots the numbers of castaways that survived would have been minimal. Thanks to the New Zealand Government’s decision to establish and maintain these depots, many people were given the opportunity to overcome the obstacles and find their way home.

![Head of Carnley Harbour. New Zealand Government steamer "Hinemoa" in background. From the album: [1907 Sub-Antarctic Expedition]; circa 1908; North, W. image item](https://media.tepapa.govt.nz/collection/197011/preview)